Any links on this page that lead to products on Amazon and other companies may be affiliate links and we earn a commission if you make a qualifying purchase. Thanks in advance for your support!

Considering the history of Civil Defence and war preparedness for the UK, Nick Spall looks at how the nation might have to cope with dangers of a future nuclear attack, how best to survive it, plus whether space technology may help to provide better warnings of any future conflicts. Also covered is whether there is a case to ensure that the UK’s “civil resilience” planning becomes more robust and effective to allow potential survival in a future World War Three.

Following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the significant deterioration of relations with Russia, many will question the current state of the UK’s “civil resilience” preparedness and perhaps be very concerned that, apparently, the nation is largely unprepared for the consequences of a nuclear attack.

Relatively sophisticated UK civil defence plans were established during the Cold War period of 1949-1991, aimed then at maintaining the continuity of government in an emergency and providing a structure for the warning, protection and post-attack caring of the population mainly via volunteer organisations.

Today it appears that only skeletal preparations and resources exist in this regard.

The case for better “Civil Resilience”

In some respects, advanced technology that has developed since the Cold War years has made the UK more alert to possible attacks.

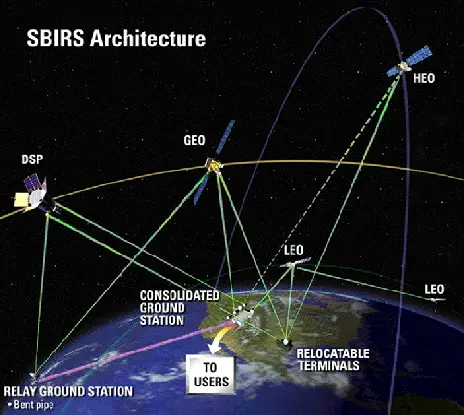

Today, sophisticated space-based reconnaissance and warning satellites monitor the skies and listen-in to potentially hostile radio traffic and command and control communications of adversaries. Via NATO links to the NORAD alert organisation, the UK is covered by several US Space Based Infrared Systems (SBIRS) orbiting satellites and these would accurately tell the UK Space Command where threatening incoming missiles were targeted, plus if the worst happened, where nuclear bursts were occurring.

The UK’s Skynet communications satellites would link the military to its assets across the world, plus allow the UK to coordinate responses with its international allies.

Through links to news broadcasting and the phone system, the population would receive some advanced warning of incoming attacks – this might be more immediate than the former siren-based approach that had existed in the UK since WW2. Assuming attacks did not completely take out all communications facilities across the country, some information would subsequently be provided about potentially dangerous radiation levels and the need to take refuge after any attack.

However to many it appears that the UK lacks the capacity and resilience to cope with potential large-scale attacks on the country, possibly involving both conventional and nuclear weapons.

Other nations, notably Scandinavian countries, Germany, Switzerland, plus internationally states including the USA, Canada and Singapore, all maintain carefully organised emergency civil protection, rescue and feeding support organisations, properly planned and funded for civil resilience operations that are directed at both civil disaster and wartime situations.

Many may ask therefore, could the UK also step up to the mark and protect its population adequately?

When was the UK’s Civil Defence organisation disbanded?

It is important to consider what has gone before in terms of national civil resilience preparedness, to assess whether the UK will now be able to effectively look after its citizens in any major natural disaster or wartime scenario, currently and for the future.

Post WW2 the Cold War period of international tension with the former Soviet Union (1949-1991) led to detailed planning for a Civil Defence system largely based on volunteer organisations. These groups included:

- Civil Defence Corps (1949-1968) – 330,000 strong at its peak in the early 1960’s, this volunteer body would provide rescue, medical, communications and transport capabilities for wartime situations. It was equipped with extensive rescue equipment, vehicles, standby generators and water storage facilities.

- Royal Observer Corps – ROC (1925-1995) – 11,000 volunteers dedicated to providing the public and the military with information on nuclear explosion and radiation fall-out levels across the UK. Operating from over 1,500 underground “posts”, detailed information was relayed to sector and group HQ’s and then passed to the UK Warning and Monitoring Organisation (UKWMO) for dissemination via public warnings. The “AWDREY” and DIADEM” automated nuclear explosion sensors would initially alert UKWMO staff of the general location of nuclear attack targeting on the UK.

- Auxiliary Fire Service – AFS (1938-68) – over 20,000 strong at its peak, the AFS was equipped with over 1,000 “Green Goddess” fire engines plus other rescue vehicles to support the regular fire and rescue services.

- WRVS – (1938 to present) – now called the RVS, this body reached 20,000 members in size during the 1960’s. It could provide mass feeding stations, local community support, medical and social work functions. In 2020 during the Covid pandemic, the RVS temporarily expanded with 250,000 additional volunteers to assist the NHS.

- “Raynet” – (1953 to present) – an amateur radio group of 2,000 members, able to provide emergency communications across the nation, as required.

During the Cold War, additional Civil Defence provisions were offered by the following:

- Nuclear war bunkers – government Control Centres – to provide continuity of national, regional and local government, several dozen underground and protected surface Control Centres were built and maintained across the UK. These were to be staffed by civil servant and local government officers during any emergency wartime situation, providing coordination with the emergency services, the military and the public, with a post attack recovery government structure left in place.

- Nuclear attack alert – Emergency Broadcasting Service (EBS) – this was operated by the BBC and in the event of an attack on the UK, following information provided from the RAF missile warning system at Fylingdales and Menwith Hill, attack alerts would be broadcast to the public via BBC television and radio. Information regarding fall-out levels and the need for protection at home was to be transmitted from studios at the BBC television and radio centres in London, an emergency studio at Wood Norton, plus from the National Seat of Government at Corsham (“Burlington”) and also from operational Regional and Sub Regional Control Centres.

- Warning units and siren alert system – “carrier units” with audio attack warnings were linked to the wider national attack alert system and these were maintained across the country in police, fire and ambulance stations, government control centres and some public buildings. Several thousand emergency sirens were available for public warnings of attack and radiation fall-out dangers. Police and CD wardens could give local warnings. ROC posts could fire maroon warnings as required.

- Public protection information – whilst the UK’s Civil Defence system did not provide for mass public shelters in the event of nuclear attack, at times of international tension extensive government advice was to be provided via pamphlets (eg “Protect and Survive”), newspaper ads, TV and radio broadcasts etc. specifically during any run-up to a conflict, for personal and family self-help shelter provision. CD warden advisors were on hand to give local advice and support as required.

- “Buffer depot” emergency stores – the government maintained extensive stores of food, fuel, emergency generators, health service medical supplies etc. Stocks were maintained for rebuilding public service telephone functions, gas supply, water and electricity company repair work etc.

- National communication system – for radio and telephones this was maintained via hardened GPO facilities and microwave transmission masts across the UK , called “Backbone”, plus the CONRAD radio system .

Whilst this mainly volunteer-run UK Civil Defence system of the Cold War years could not approach the level of protection offered by nations like Switzerland, Sweden and the USA where extensive public shelters were provided for much of the population, it did at least offer some hope and continuity for the many potential survivors of a possible nuclear war.

Indeed, it was considered at the time that if the nuclear exchange was relatively limited in extent, many millions in the nation would have survived – they would then have needed extensive government support and advice, particularly for food and water provision, medical services and security provision during any post-war recovery period.

Current Civil Defence plans – “civil resilience”

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and end of the Cold War years, successive governments closed down most of the UK’s Civil Defence infrastructure.

The ROC and UKMWO were disbanded, hardened government control centres like the Kelvedon Hatch Regional Centre, now a museum, were sold off and comprehensive national/local government emergency planning was slimmed down. Beyond coping with relatively limited disasters such as terrorist attacks or nuclear reactor accidents, traditional “Civil Defence” has now virtually ceased.

For the UK, the maintenance of an effective independent national nuclear deterrent via the Trident submarine fleet was generally considered to be enough to deter any aggressor nation launching a major conventional or, indeed, nuclear attack on the country. Hence, for the post-Cold War era, very limited investment in civil defence/resilience spending was considered necessary.

It should be said that much of what now remains in place for wartime “civil resilience” preparation is relatively unknown and restricted in public information terms.

As far as can be ascertained however, civil resilience appears to now be in a relatively “skeletal” form – it is, apparently, not designed at present to deal with the possibility of future large-scale conventional or indeed nuclear attack on the UK.

What does the UK’s Civil Defence now provide?

Civil resilience in the UK appears to rely on the following measures:

- Civil Contingencies Act (2004) and the National Security Strategy (2010) – these aspects of government legislation and policy consider the need for civil resilience to be based on a National Risk Register (NRR). Maintained by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat (CCS) as set up in 2001 within the Cabinet Office, the current NRR prepared in 2020 sets out a risk assessment that categorises three levels, “priority risks” (eg terrorism and flooding), “medium risks” (eg chemical, biological or nuclear war) and “lower risks”( diseases and other natural disasters.)

From this analysis, government departments are required to prepare plans to deal with the identified risks. Significantly, large-scale conventional or nuclear attack on the UK is not currently considered to merit a Category 1 “priority risk” status.

- Emergency Planning – for the current system, under the Contingencies Act civil protection duties are currently placed on “Category 1 responders”, (i.e., the police, fire and rescue and ambulance services.) Clearly, many would argue that in the event of a major disaster or war situation the current responder resources would soon be overwhelmed.

- Emergency government/civil communications – the Electronic Communications Resilience and Response Group (EC-RRG) is currently tasked with providing a National Emergency Plan for telecommunications. It is made up via a grouping of private telecoms operators, coordinated by Ofcom. These private companies are required to support devolved administrations and government departments. A “National Emergency Alert for Telecoms Protocol” exists and the telecom operators are expected to work together in an emergency – a “Resilience Direct, High Integrity Telecoms Systems” plus a “Mobile Telecoms Privilege Access Scheme” operates – the Cabinet Office gives guidance for a “diversity” of communications.

- Nuclear attack alerts: National Attack Warning System (NAWS) – this national alert system via TV, radio and the phone system was completed in 2003, costing £200-400,000/year. From 2020, this is understood to have been extended to provide potential emergency alerts to mobile phone users – many would have received NHS contacts regarding Covid pandemic covering isolation requirements and vaccination arrangements for example. NAWS is understood to be capable of broadcasting an attack alert message to the public within 60 secs. of a warning, as triggered by an analogue message system from RAF High Wycombe following the detection of an impending strike, via the UK Space Command’s RAF Fylingdales phased array early-warning radar and Menwith Hill monitoring equipment, plus available US/NATO linked Space Based Infrared Systems (SBIRS) satellite monitoring information. The BBC is still able to broadcast warning messages via its TV and radio services, though this would be relatively slow, possibly up to 10 minutes after receiving an alert. Post attack messages via BT and other telecoms operators might be achievable as part of NAWS.

- Central government nuclear bunkers- the Whitehall bunker known as PINDAR exists, complete with COBRA function facilities, plus a national emergency broadcasting provision. The former extensive “Burlington” National Seat of Government of the early 1960’s at Corsham has now been mostly sold off, although it is understood that the much smaller MoD “Corsham New Environment” (CNE) facility close by would provide national government and military communications functions

- Local Resilience Forums (LRF’s) – these groupings are located within police areas and aim to coordinate emergency services, local authority functions, the NHS, the Environment Agency (EA) and community groups. They respond to the NRR assessments and attempt to plan for emergency risks as required but are not designed to address major wartime scenarios.

Assessment of existing Civil Defence/resilience provisions

At present, faced with a major attack on the UK, either via conventional or nuclear weapons, many would consider that the existing emergency services and civil resilience provisions would be inadequate to cope with a conflict situation.

The war in the Ukraine has illustrated what damage could occur to a UK city, faced even with just a conventional war situation.

In a “first strike” conventional weapons attack – well explained via military historian Mark Felton’s analysis video “Could Putin attack Britain?” – accurate cruise and Avangard-type hypersonic missile impacts on military, power, communications and key transport interchange targets would not only seriously damage the nation’s ability to operate power, adequate food distribution or telecommunications, but also the UK’s rescue and medical services would be completely over-stretched attempting to handle the inevitably very large numbers of casualties.

Nuclear war effects on the UK

Some will have seen the portrayal of nuclear attacks in movies from the past, including “The War Game” (1966), “The Day After” (1983) and “Threads” (1984).

Even in the event of a limited nuclear exchange against the UK, matters will be extremely bad – in this scenario, key issues for the UK to address would be:

- Lack of extensive rescue and medical treatment capabilities via support staff, reserve equipment and rescue vehicle numbers.

- Attack warning provisions for the public – the former warning siren system is no longer maintained on a large scale, except in areas of potential flooding or near nuclear reactor sites…..one argument apparently being that widespread double-glazing makes the sirens difficult for many to hear. The current BBC/telecom measures however are apparently unrehearsed and largely untested.

- Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) effects could wipe out warning and post attack communications, unless hardened public broadcast and emergency receivers are adequately protected (via “Faraday cage” technology etc).

- Limited radioactive fall-out warning – no ROC-type posts or UKWMO information will be in operation to advise the population on the need for shelter. It is uncertain if any current automatic military sensor information is to be made fully publicly available.

- No occupiable and secure government control centres are in place. Coordination of community functions at Regional, County or local authority (LA) levels now appear non-existent.LA Emergency Planning Officers do not appear to have the resources to cope with large scale war situations.

- Reserve national food and fuel stocks appear very limited and unplanned.

- Post attack recovery planning and future community structures are apparently not in place.

- Public information regarding the likely effects of nuclear weapons, shelter construction, attack and fall-out warning provision, food and medical availability in the event of a conflict and local government/emergency services is apparently not available, certainly for the near future.

Electro-magnetic Pulse (EMP) effects

When a nuclear device is exploded, powerful EMP effects would occur even at some distance from the ignition point disabling electrical circuitry and grids. This may result in the loss of car engine functions, power supply grids and electronic communication devices such as transistor radios, mobile phones and sensitive electronic equipment. Old valve radios were, ironically, better protected than today’s integrated circuit devices.

A single but very powerful 2 megaton nuclear detonation high over the North Sea could cripple both civilian and military electronic equipment across the country, ruining government communications and indeed any warning system for the population.

Post-attack chaos would result from such an action by an aggressor nation.

Hardening sensitive electronics via “Faraday Cage” screens – effectively carefully designed protective wire cages – is possible and, presumably, the UK’s military would be prepared for this eventuality. For the general public however, no real electronic protection advice currently exists and the stock of standby back-up communications and power transmission equipment appears absent for the UK.

Where is the safest place to be during a nuclear attack on the UK?

Due to the relatively small size of the UK and the density of potential conventional or nuclear strike targets, many would argue that nowhere is really safe from the effects of a nuclear conflict, particularly if it reached the level of a widescale city-target strategic exchange.

The UK’s government’s Civil Defence advice from the Cold War period was that the population should remain in their homes rather than attempt an evacuation to an alternative location – this policy would most likely remain in place for any future nuclear war scenario.

However, assuming there was some public knowledge of potential key military and government command and control targets, it might be arguable that pre-attack evacuations might be achievable by the authorities. No doubt though, information about those targets would be highly restricted and time would not be available for the population movement process to effectively occur.

Alternatively, a personal “self-help” approach might be to assess whether a home location was close to any of the following key likely target locations – these might include:

Military radar and major early warning sites

– Major military and civilian air bases/dispersal airports

– Key naval bases

– Command and control centres (the few protected military/ government bunkers in the UK)

– Major ports

– Key oil / gas refinery infrastructure, pipeline connections and storage facilities

– Key power stations (conventional and nuclear)

– Major transport interchanges (road and rail)

Attacks against city population centres would appear to be the final scenario of any nuclear exchange. It might be that an aggressor nation may try to detonate a “warning” weapon over an urban area, to attempt to intimidate, terrorise and eventually control the nation’s political resolve.

For individuals faced with a safe location choice, it might be possible to plot all the likely attack targets and conclude that blast damage and radiation dangers would be at their least in remote country areas, perhaps in locations such as central Wales or the Highlands of Scotland. Remember however, radioactive fall-out moves with the wind. Although the UK’s prevailing wind direction is from the south-west, winds do vary across any season and an easterly wind for example taking fall-out from attacked military airbases on the eastern side of the country towards the west would affect millions living in the major key cities of the central UK, even to more remote Wales. Similarly, central Scotland would suffer the consequences of fall-out moving across the UK from the south, assuming a southerly wind system occurred at the time any attack.

An additional reality is that major roads and railway links would most likely be closed for military use in the run-up to an international conflict and movement would be extremely difficult in any event.

The “stay-put” advice from government may be the only viable alternative for householders and families faced with an emerging war situation.

What do you need to survive a nuclear attack?

Assuming there is a lead-in period before a major conventional or nuclear attack on the UK, there are in fact many actions that can be undertaken to seek the best chance of survival and prepare for the worst.

Advice from the UK’s “Protect and Survive” pamphlet was received somewhat sceptically in the 1980’s, but much of it appears logical and practical. Assuming no personal underground shelter or bespoke fall-out room was available – in Singapore and Switzerland, for years all new buildings have to have bespoke shelter rooms as part of national Building Regulations – the advice included:

- Home protection: choosing a central ground floor or basement shelter room with maximum material thickness in any dwelling-house is advised. Outside windows should be blocked around the shelter if possible, using whatever is available including boards, slabs, bricks or dense bags of material.

- Inner refuge: inside the room an “inner core” should be built for the inhabitants, using available boards and tables and piling as much dense material over it as possible – even stacked books can give some protection against harmful gamma radiation.

- Water: water is essential for survival and on average adults need at least 2-3 litres per day. Pre-attack, all available bottles, containers drums, buckets and even the bath should be filled and covered up, mostly being kept in the shelter room if possible.

- Food: tinned, packet and bottled food for at least 14 days was recommended, to last the likely period as required in the shelter room.

- Other essentials: these would include a radio (ideally wind-up), torches, candles, matches, batteries, a toolkit, first aid materials, medicine supplies, tin openers, cutlery, disposable bowls, plastic rubbish bags, plus a “grab-bag” with key family documents, were advised for the room.

- Radiation meter: not available in the Cold War years, cheap battery-powered personal radiation meters can now be purchased online. These measure harmful gamma radiation, usually in micro/milli-Sieverts. Danger level warning alarms can be set on the devices and instructions are provided on what dosage rates are tolerable for radiation environments.

- Potassium iodide pills: some nations, possibly even the UK, stock these pills for nuclear emergency events – they are intended to prevent the build-up of radiation in the thyroid gland and are potentially important for children in particular.

Home protection measures that were also advised in the UK’s Cold War years included white-washing external windows to reflect the heat flash from a nuclear explosion, switching off gas supplies and monitoring the radio for warning information every hour. Sheets hung over doorways would reduce the ingress of potentially radioactive dust.

In blocks of flats, a shelter room location in the basement or centre of the building was advised.

Long term planning

After any potential nuclear attack, many considered that survival was not possible, with the attitude being that “the living would envy the dead”.

Indeed, if there was a large-scale nuclear exchange, post-attack life would be extremely difficult for the survivors – martial law would no doubt ensue, severe food, fuel and power shortages would occur probably for years after, plus harmful radiation would travel around the globe, affecting nations outside the war zones and, ironically of course, even the aggressor state itself.

The feared “nuclear winter” consequences of high-altitude dust from the conflict reducing global temperatures and the impact on the agricultural systems of the world would be significant.

However, in the situation involving a limited conventional or even tactical nuclear war, significant parts of society would come through and their post-war needs would require planning and resources.

A Civil Resilience Corps (CRC) – the potential benefits

What is the case for the UK possessing its own in-depth civil resilience system?

It should be noted that a solid volunteer tradition exists in the UK. During the early stages of the 2020 Covid pandemic for example, enthusiastic citizens immediately offered their help – the Royal Volunteer Society (RVS) received over 750,000 applications from those keen to support the health and community services at that time.

One option to enhance the UK’s preparedness and security for the future is that the government implements measures to set up a new national “Civil Resilience Corps” (CRC), with a recommended initial size of approximately 250,000 members. Its brief would be the following:

- Establish, train and maintain a group of volunteer members who are available during future national emergency and disaster situations, to provide a range of civil resilience support skills.

- Work with existing government emergency services and the military, to provide public warning, rescue and support activities, potentially during wartime situations if required.

- Supported by the new CRC, maintain and operate as needed national reserves of emergency food and medical resources, including fuel, water distribution and communications support equipment, to properly plan and provide for any national disaster recovery process.

The wider benefits of a future “CRC” would not only be the practical ability of the nation to effectively survive major disasters and war situations and to recover as a democracy, but also to allow the UK to enhance its sense of neighbourliness and cooperation as a modern and compassionate society.

A fully established CRC of up to 250,000 volunteer members could address many of the civil resilience problem issues raised, providing a relatively low-cost approach to matters including emergency advice to the UK public, alert methodology, rescue functions, first aid /paramedic treatment, post-attack recovery support and the security of food, water and fuel supply stocks.

The volunteer CRC could also operate during non-conflict civil emergency situations, as a trained rescue and support organisation, working in coordination with established “first responder” services, as well as being a community grouping of like-minded individuals committed to public service.

Importantly, the CRC would create public confidence and relative national peace of mind by showing that the UK does take potential disaster planning seriously and is committed to volunteer and community-led organisation at the local level.

The enhancement of neighbourliness and community cooperation are further strong benefits that the CRC might provide for society.

Finally, a well-run CRC would also send a clear message to any potential aggressor that the nation is robust, fully determined to maintain its democracy and national identity in the face of adversity.